Greetings all,

This is Part 3 of my ongoing posting of my application for Program Coordinator for the Spring 2018 Program Coordinator selection.

If you want more context on my answers, you can head to Part 1 or Part 2.

I actually want to start this off by providing some context and reasoning for what I am publishing, and why, because not everyone has it.

Oh, and fair warning, this is a pretty long article. You are in for an extended pre-commentary, then my verbose responses.

What I am publishing, why, and why now?

I’m publishing purely my own words, my responses to the interview questions that are part of the Program Coordinator selection process.

I have a variety of reasons for this, and I am going to dig into a few of them here. Note that a lot of these don’t apply to the other Program Coordinator applicants. They are writing specifically for the selection committee, and their expectation going in was that this would be private. If the committee publishes their application, that’s a breach of trust. If people push them to publish, that’s changing expectations. I don’t expect anyone else to publish anything. I’m doing this for my reasons, not holding others to these reasons.

First, I want my application text to be fully open, regardless of if I get the role or not. If I don’t get the Program Coordinator role, publishing my answers afterwords looks a little spiteful. “See what the committee rejected, look, it’s totally worth it” is the message I’d get from that kind of publication. I don’t want to give that message. I want to put my answers out in public, and my reasoning prior to the announcement of anything, because I don’t hold any spite for the committee. In fact, I respect them and I’m not going to kick up a fit. I’m demonstrating I’m publishing regardless of the outcome by publishing before the outcome.

I believe that the Program Coordinator role is a public one, and the people in the role can’t hide their decisions. Sometimes they will have to make choices about what information to share with the public – the role comes with an NDA, and sometimes gets some limited information from either Wizards of the Coast or other parts of the judge program that can’t be shared until some later date. Demonstrating that I know what is acceptable to share, and demonstrating I can be a strong public voice and take ownership of my words and actions is absolutely part of what I want to show as part of the Program Coordinator process.

I also don’t want to put this off again and again, then declare I won’t finish it, or hope people don’t remember or stopped caring. You can see on this very blog that I started stuff and did not finish it. That’s very normal for a lot of people, and normal for my history. I don’t want to put things off related to this role. I believe it is important, and I can’t just ignore or walk away from this.

Oh, and there are no public Program Coordinator applications from people that did not get the role. Riki and Riccardo published their applications, but they got the role. I am personally fine with my application being a demonstration of a failed application. We really hold up success as a big deal in the judge program, but failing and getting back up and doing stuff is very important too, and if I fail I want there to be some use out of the effort I’ve spent.

I’ve also heard some commentary about my timing for publication. I don’t have any results yet. I wrote my answers, did some back and forth with Riccardo about them (which I’ll talk about below), and spent some time writing this post. I’m not trying to force announcements, or info. This is just the timing that works out with my schedule and writing some commentary on the questions and answers. I have no inside info about the status of my application or any application.

The Questions

This is the set of questions I got from the committee:

- It may seem that your application presents you as “a PC for the US judges” only. Don’t you believe that PCs should be a single group for the entire judge program?

- Your application seems akin of applying to a “super RC” post, while you clearly define in your answers that PC and RC are not responsible for the same spheres. Could you elaborate on that ?

- Do you believe there is currently friction between US judges and EU judges? If yes, how could PCs help removing the friction?

As you will see below, I changed the order of the questions, and then asked for clarification on one of them.

I’m going to take an aside here before I post my answers and talk about what I think the committee was concerned about in my prior applications and what these questions mean, so you can see where I came from in my (really lengthy) answers.

Pre-Commentary on Question 1

1. It may seem that your application presents you as “a PC for the US judges” only. Don’t you believe that PCs should be a single group for the entire judge program?

I moved this question after Question 3, because I really wanted the committee to have the context of the Question 2 answer before they got to my answer.

I believe the committee has a very legitimate concern here, that there would be people working specifically for a faction of the judge program within the Program Coordinator group, and they wanted me to address this concern. I also think that this is a question that is different than I would ask about this concern, because it makes some assumptions about my application and about the Program Coordinator role that I personally feel are unwarranted.

The question makes an assumption that the Program Coordinators should be a single group “for” the entire judge program. That’s a really strange assumption. The Program Coordinators do work that is program-wide, but the phrasing here makes it seem like they somehow transcend their histories and should ignore the groups they have historically worked well with…or something. I’m not entirely clear on what the question writer thought, because of the brevity of the question.

It also assumes that I’m saying something about how I would only represent the United States in my prior application question. I think that is a misreading of my answers. I specifically say how the current group of Program Coordinators does not address a lot of concerns for a fairly large group of judges, and how I am in a position to do so more effectively than the current Program Coordinators. This assumption based on a misreading of my other answers is an interesting one. I obviously disagree with it, but I can see how that impression came across.

Pre-Commentary on Question 2

2. Your application seems akin of applying to a “super RC” post, while you clearly define in your answers that PC and RC are not responsible for the same spheres. Could you elaborate on that ?

I did not actually answer this question as a stand-alone answer. I also had a number of problems with it. Riccardo and I had a long discussion about this question in an online chat, and his explanation made it clear that the committee had the information they needed and why they wanted to ask the question. It did not solve my full confusion, but that’s fine.

My confusion stemmed from not understanding where in my prior answers I gave the impression I was applying for a “super RC” role.

I asked about this, and Riccardo took a look, asked the committee, and admitted that the question was in large part motivated by the same concerns as the prior question – the asker felt that I was applying to be a PC of the US. He said they got enough information from my other answers that the question was addressed to their satisfaction.

Pre-Commentary on Question 3

3.Do you believe there is currently friction between US judges and EU judges? If yes, how could PCs help removing the friction?

This is the meatiest question here, and it is a softball question, because the answer is clearly “yes” followed by a barrage of ideas. My commentary is short here, because I spent 3000 words on the question and I don’t feel the need to say much other than it really got me fired up to think that someone believes that the answer to the first part could be “no”.

My Answers

3. Do you believe there is currently friction between US judges and EU judges? If yes, how could PCs help removing the friction?

The answer to the first part is “yes”.

The short answer to the second part is “ensure that US judges are listened to and represented strongly in leadership groups, and make these groups work in a way that US judges intuitively understand”.

There is obviously a lot more going on than this short answer covers, and I’m going to trot out some stats, some gut feelings, and some information I’ve received from other North American judges to talk about the judge program as it stands right now and some of the structural and logistical challenges facing us all.

I am also going to talk specifically about North American judges and European judges. Latin American and Asia-Pacific judges: know that I care a lot. I want you to be in leadership roles too. The issue is one of proportions and it is super clear that the North American judges are currently in a bad place, so I’ll be talking about the problems from a really North American perspective. I’ll probably end up having to do some really deep thinking and figuring in the future, because I am not wholly certain what the best worldwide solutions to some of the problems I am posing are…I just know they are deep problems and North America has the worst symptoms.

Stats and a Starting Point

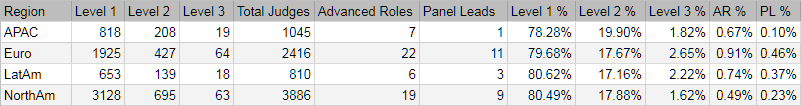

I’m going to lead with a table, so you have some data up front.

On Monday, February 12th, I pulled down the JudgeApps master judge list, and did some data mining of it. I came up with this set of numbers:

Note that by the time you read this it will already be out of date – 6 US and 2 European L3s will be decertified, and the L1 and L2 numbers are going to be substantially different due to maintenance.

My methodology was: I did by-region counts of every level in JudgeApps, and then divided those regions into geo-regions and did the summations. There are exceptions to every number (for instance, Jeff Morrow and Daniel Kitachewsky are still listed as L3 Panel Leads), and if someone has two Advanced Roles they are counted twice – the count was number of roles, not number of people with Advanced Roles.

This is the breakdown of Grand Prix for 2018 by geo-region:

31 North America

16 Europe

3 Latin America

10 APAC

For the Pro Tour 25th Anniversary, there are 1,613 PPTQs. 673 of these are in the United States. That’s 42%. PPTQs are a good barometer for local Organized Play, and demonstrate we have the base of events and judges to support more leadership.

I’m going to be calling out some problems these stats illustrate, and pointing back to the numbers as starting places.

The L3 Problem

North America is having a problem making L3s and keeping quality L3s active and engaged. A bad one, and we can correct it, but it will take some work.

You can see the raw numbers – pre-maintenance, North America has 50% more total judges, but the same amount of L3 judges as Europe. The Grand Prix breakdown above is also fairly disconcerting when you compare it to the L3 numbers. We have nearly twice as many Grand Prixs in the US, but the same pre-maintenance number of L3s.

I have had some lengthy discussions with John Brian McCarthy about this, and he has a lot of stats at his fingertips about L3 pass rates and historical in-region and out-of-region panel lead performance. I had an extended digression here about this, but there is a tangled mess of problems and we aren’t really close to solving any of them. I don’t want to turn this section into an extended aside on specific problems with the L3 process, but I do want to point out that there are problems and there are hard numbers and statistics to support them.

L3 production has problems in North America, and we have a much lower proportion of L3s relative to the number of total judges than the program probably needs to sustain itself. This has some huge impacts on the nature of GPs, RPTQs, and other events that have need or desire for L3s.

This is also a negative feedback loop. The best L3s go to a ton of shows, and get burnt out, and step back…and attrition goes up.

We are so bad at making L3s that the USA – Southwest region, the third most populous region worldwide, had no L3s that were willing to step up as Regional Coordinator. (Brazil had this problem as well – they also have systemic problems with L3 creation, but for different reasons than the US.)

We have some deep and systemic problems in North America with the L3 process. I went stat hunting because I had an intuition about this, and those stats showed me a reality that matched my intuition. My focus on being a Program Coordinator from the US stems from seeing these issues, talking directly with the judges facing them, and realizing that the kind of close perspective that informs that intuition is not something a more distant Program Coordinator would be able to replicate. The amount of European engagement seems higher, and Europe is making and maintaining L3s better than North America, at least from what I can tell.

The Trust Network Problem

Along with problems making L3 judges, many of the internal operational and leadership roles of the judge program have gravitated to Europe.

This is much more than just “we have no North American Program Coordinator”. This is about Pournelle’s Iron Law of Bureaucracy, and it is about who controls the internal structure and maintenance of a group that exists for a particular purpose.

There are 13 Spheres. 9 of them are lead by Europeans.

Consider the gatekeepers of leadership positions in the Judge Program. The L3 Pre-Event Interview Lead, L3 Testing Manager, L2 Tester Certification Manager, and L2 Team Lead Certification Manager are all Europeans. The RC leader and GP HJ leader are Europeans. The last PC selection committee was comprised of 3 Europeans and only 1 North American, and the committee before that was 5 Europeans and 2 North Americans.

This is not an indictment of any of these fine people. They are as qualified as anyone is for their roles. What they aren’t is physically close or socially connected to North American judges.

We have consciously built our program on a trust network. This was a deliberate decision with the NNWO. There are implications of that which are only slowly becoming clear right now.

Our trust network in a lot of ways centers around and radiates from Regional Coordinators, and where it does it works pretty well, because Regional Coordinators are by their nature tied to regions that aren’t too much larger than Dunbar’s Number. Finding judges and running conferences works quite well worldwide.

There are a number of places where the trust network that keeps our program functioning does not center around Regional Coordinators, though. Those places are primarily in project work and program maintenance. As you can see from my numbers above, the number of Europeans in named management and upkeep roles greatly outweighs North Americans.

Getting into one of these roles has elements of black magic. You need to know someone in a key role and you need to demonstrate your willingness to help them and step up. You build social capital in the trust network, and get moved into a key role. This means it is an easier path for Europeans to get into these roles, because they have closer ties to other Europeans. When Ben McDole stepped down as lead of the Education Sphere, two European Judges were selected to replace him. When Johanna Virtanen stepped down as head of the PIC, a European Judge was selected to replace her. When David de la Iglesia stepped down from the Social Media Sphere, a European Judge was selected to replace him. And when Daniel K stepped down as Level 3 Testing Manager, a European Judge was selected to replace him.

We also have fewer people that step up and do this kind of program work in the US overall. Sebastian Pękala has been really pushing more US RCs to be part of leadership and selection committees, and encourages us to push more of our judges to be part of these things as well, because our participation is low.

The low participation is both because a lot of North American judges don’t automatically gravitate towards the consensus system that drives a lot of the management roles in the program (which I’ll talk more about in a bit), and because we have fewer L3s for more event work than Europe does. So the most active L3s tend to get in event loops and don’t spend their time doing program management work.

Consensus vs Tyranny

There is a philosophy of leadership problem that has been causing friction within the judge program, and it should be brought out into public and displayed so we can understand it better.

The core conflict is in how we manage and motivate groups of people, and how we get things done.

I’ve shorthanded this to “Consensus vs Tyranny.”

In the Tyranny model (which is what dominates in North American-run projects like Exemplar and JudgeApps), one person is the Tyrant. They listen to input, and solicit it, but ultimately the key decisions rest on the person in charge, the Tyrant.

Bryan Prillaman is an exceptional Tyrant. He acts in this role because he feels there is a job that needs doing, and he does not want to see it left undone. He solicits help, assigns out jobs, but when things blow up, everyone knows that Bryan *is* Exemplar. The identity of the project is connected directly to him and his decisions.

In the Consensus model (which is what dominates European-run projects like Advanced Role selection or the Judge Conduct Committee), there is a leader, but they are a guide and not a dictator. Call them the First Speaker. They open discussions and close them, but they push for consensus rather than just making a final call themselves.

Cristiana Dionisio is an exceptional First Speaker. I’ve been part of multiple JCC related things since she took charge, and she had driven conversation, called votes, and forced people to make use of their voices to really get an idea of what each person cares about and wants to have as a result. She acts in this role because she feels that things need multiple voices to really be a decision by the group.

I want to say that neither of these models is the “one true leadership method.” Both have strong leaders that act using them, and both are useful in different circumstances. The JCC is not the place for a Tyrant, and neither are selection committees.

North American leaders and followers tend to gravitate towards Tyrant leadership, and European leaders and followers tend to gravitate towards Consensus leadership, at least in my experience in the judge program.

Internal management tends to be really Consensus driven in the program as well, which means Europeans gravitate towards it. It’s a little chicken-and-egg like, because the system evolves both in process and the people managing the process, in steps. But this is where I see us now and where I see us going.

The problem is twofold – North American judges just don’t volunteer for Consensus leadership positions as much, and we are also generally worse at them. We really need to be aware of this and tailor our systems to understand this going forward. Choosing methods of management and leadership that don’t resonate with the members of the program is a good way to subtly make those people unhappy.

Social Problems

The US and Europe are very different social climates. Neither is wrong, but they have different pitfalls and different standards.

I could go into a lot of things here. I could talk about sexual harassment and how the US is undergoing the #metoo movement. I could talk about crime and punishment and how the US has a sex offenders registry people can’t ever get off of. I could talk about legally protected speech and how far the US will go to protect speech. I could talk about politics and how messed up any kind of political discussions are here. These aren’t exhaustive, but they are illustrative.

The leadership of the judge program can’t ignore these social standards. I firmly believe that decisions should not be made by one person only versed in their local region, but should be passed through the lens of people from different cultures so they can each own and modify a facet of it.

This necessitates people that understand their regions and how things touch on them well, and who speak from that expertise.

Legal Problems

This is the least controllable by the judge program, but it absolutely needs to be brought up.

European leaders in the judge program know European laws and the realities around them quite well. Like all of us, they tend to craft solutions for problems that match the things they know and understand.

Because Europeans lead the program right now, decisions tend to be rooted in laws and culture based in Europe. That works super well for European judges, but not for everyone everywhere.

To give you an idea of how different the social and legal structure is in Europe vs the US (Canada is different yet, and I’m deliberately excluding them from this illustration), at the end of 2016 I was the only US member of the attempt to do L3 Maintenance. When we pushed out our data to each judge, one US judge (who happens to be a lawyer) ended their first message to me about the situation with “I’m not above getting a court order to discover who is libelous”. I read that as “tell me who said these things or I will sue you”, and other people I showed it to read it the same way.

This is an unfortunate fact of life in the US, one that Europeans don’t always internalize. Lawsuits aren’t the first option for many, but they are always an option, and we don’t have a “loser pays court costs of the winner” system. Both parties pay. Getting sued, even if you win, can be ruinous. And it’s just the nature of how it works here, so we have to accept it as something we must plan around.

When program leadership makes statements or plans that ignore this reality of the US, it makes the US judges feel as if our experiences are being ignored. If someone feels leadership is ignoring them, they tend to check out, and that causes a volunteer organization to massively suffer in motivation. There is a recent example of this in the Program Coordinator statement on background checks. The biggest response from the US judges I know was that this seemed really inapplicable and questionable advice. David Hibbs talks about this extensively in a blog post and says it much better than I do.

The lawsuit against Wizards of the Coast is also rooted in the US, but has worldwide impact, and that is felt differently everywhere. In the US, the impact has been widely felt at all levels, with Tournament Organizers making efforts to avoid classifying judges as employees from the national level down to local stores. It’s changed the nature of judging in the US to a significant extent because the suit has provided a template for others to make similar legal attempts.

Conclusion

There’s a lot more I could say here. I could probably double or triple the amount of words here and still have more to say on the tension between North American and European judges, and the systemic problems we have within the program. Some are big issues, some are small, but they are all there, and the Program Coordinators need to take them into consideration.

1) It may seem that your application presents you as “a PC for the US judges” only. Don’t you believe that PCs should be a single group for the entire judge program?

My intention isn’t to be a Program Coordinator “for” US judges. It is to be one “from” the group of US judges.

I speak above about the problems and divides between different areas. For the Program Coordinators to truly represent and be a group for the whole judge program, they need voices from different parts of the judge program.

I feel the need to present the US voice I spoke about, and I feel the need to figure out ways to act with others together to form a group that does act for the judge program all together.

I also think that failing to make use of the strengths and knowledge of people in the Program Coordinator role is an imminent pitfall of the “for the whole judge program” philosophy. Program Coordinators don’t transcend their histories and knowledge. They take that history and knowledge and use it. This is the case for anyone in any role, but doubly true for top leadership.

My strengths are my grasp of data, my willingness to do technical and logistical work, and my knowledge of the United States and the judges here. If I did not play those up I’d be doing my skills and knowledge a disservice. I would also be failing to present you with the benefits I would bring to the role.

This means you know what you are getting, and where my positives lie relative to other candidates. CJ has quite similar knowledge of the US, and he would be great as a representative and as a knowledge tool for the Program Coordinators to tap – ignoring the knowledge CJ and I have and dismissing our location is a mistake that fails to serve the 3886 US judges I called out above in the stats.

Wrapup

So there are my Stage 3 question and answers.

I want to really thank Bryan Prillaman, Jacob Milicic, my wife Ruth, and John Brian McCarthy for doing some proofreading and assistance on these answers. Nobody does their roles alone, and having friends (and a wife!) like these make me look really good when I lean on their help.

As usual, if you have questions, comments, or just want to chat about stuff, feel free to comment here, drop me an email, or message me.